Note: Apologies for neglecting this newsletter for so many months. The second half of 2023 was a challenging time for me, and I have been preoccupied with teaching and two book projects (more on that forthcoming). As I head into summer, I look to give this newsletter greater attention. Thanks for subscribing, and many apologies.

I have been inundated with analogies to 1968 in recent days. I am sure you have read a few of the essays that tell us why 2024 is not 1968, or why the 1968 election is a guide for understanding the outcome of the 2024 election. 1968, we are told, offers lessons to be learned about how to protest, when to protest, the meaning of protest, and the repercussions of protest. This was to be expected, I suppose. The mass student protests against the Gaza War across American universities (including my own) were bound to provoke references to 1968 and the student protests to end the war in Vietnam that year.

I confess I have little faith in the supposed power of historical analogies for illuminating the present. Most historians do—or should. I used to dabble in them, much to my regret. History informs, contextualizes, exposes and disarms the “unprecedented.” But it should never analogize. When it does, assumptions, heuristic judgments (often misguided) and wistful prognostications often follow. Clarity does not derive from analogies.

And when it comes to the specter of 1968, I am even more skeptical of its invocation as mirror, or guide, to the present. The metaphor of 1968 is overused; it has become a trope, trotted out whenever it looks like American society is in disarray, torn asunder by generational schisms and democracy in the streets.

Rather than falling into the familiar trap of “this is just like the 1960s,” I think it is better to place the recent student protests—and the broader divestment movement—in the greater context of twentieth-century American history.

To do that, I’ll rely upon Richard Hoftstader, the great Columbia University historian and author of the 1948 book The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It. Few historians today accept Hoftstadter’s conclusions outright—and the subtitle of the book reflects the outdated, gendered norms of the profession during the mid-twentieth century—but his legacy still shapes the historical profession. The American Political Tradition, a history of reformist politicians from Thomas Jefferson to Abraham Lincoln to Franklin D. Roosevelt, was his first book, and a good one—although I personally prefer The Age of Reform.

Hoftstadter was known as a “consensus historian,” someone who searched for common themes in U.S. history to unite disparate time periods and figures in a singular narrative. Looking at American of history since 1776, Hofstadter, according to Christopher Lasch, felt that there was a “lack of serious ideological conflict in American society.” Hofstadter deemphasized political strife among Americans and argued that “the sanctity of private property” and its place in a “beneficent social order” characterized U.S. history. The “business of politics,” above all, was “to protect this competitive world, to foster it on occasion, to patch up its incidental abuses, but not to cripple it with a plan for common collective action”—i.e. socialism.

Hoftstadter’s book resonated at a time when the United States sought to cajole and rally the American public—and the global public—to support its fight against Soviet communism. While he rejected a “radical” tradition in American politics, Hoftadter captured an enduring reformist impulse in the figures he wrote about.

Which brings us to divestment.

Anti-apartheid activism in the 1960s laid the groundwork for the modern divestment movement. But divestment on college campuses also has origins in the opposition to the Vietnam War, and the student-led protests against the war.

The earliest, and largest, efforts at divestment targeted the Dow Chemical Company. Dow Chemical made napalm, the highly flammable, petroleum-like substance that went into the incendiary bombs dropped on Vietnamese civilians during Operation Rolling Thunder between 1965 and 1968. When the bombs exploded, the flaming napalm stuck to everything: clothes, skin, hair. Men, women, and children suffered painful, horrific deaths from the bombs. Napalm turned Vietnam, in the words of activist Daniel Berrigan, into the "Land of Burning Children.”

Dow recruited its future employees on college campuses, the earliest and persistent sites of the anti-war movement in the United States. Students at the University of California, Berkeley first tried to force Dow off its campus in 1966, and activists at other campuses followed their lead, with students at Brown University even demanding that the university “divest” from Dow.

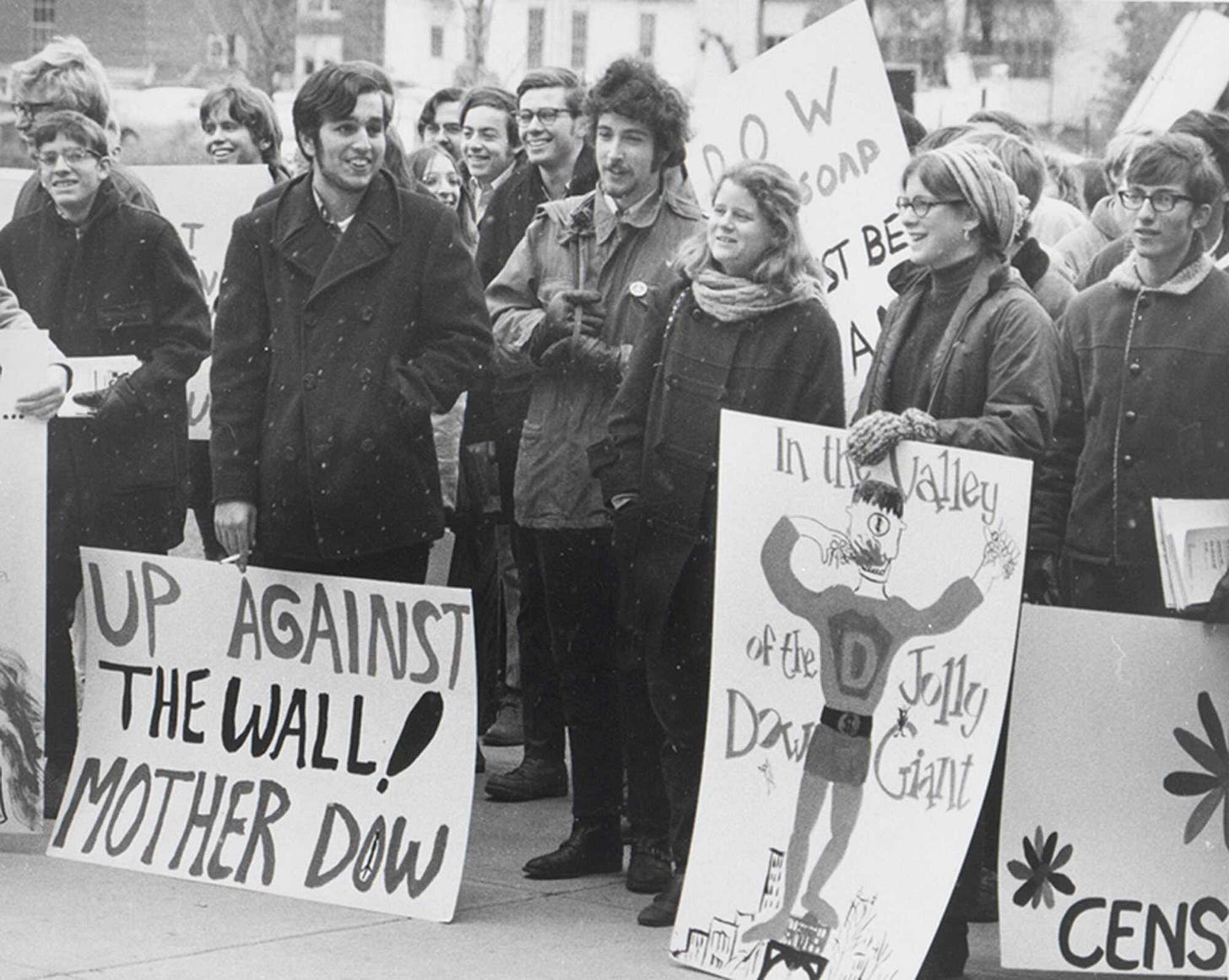

On October 18, 1967 students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison organized what became known as the “Dow Riot.” Dozens of students rushed into the Dean’s office and occupied Commerce Building (now renamed Ingram Hall) where Dow conducted its employee interviews. The protestors refused to leave “until the university agrees not to allow Dow to recruit on this campus.” The administration rejected the protestors’ demands. The university’s chief of police called in the Madison police for backup, who had no precedent for dealing with non-violent student protestors. But they became riot police once they entered the campus. Madison police beat protestors with Billy clubs and tear gas was used for the first time at a campus anti-war protest. 47 students were sent to the hospital.

The “Dow Riot,” October 1967

Dow soon became notorious for enabling mass atrocities in Vietnam. “Next to LBJ [President Lyndon Johnson], [Secretary of State] Dean Rusk, and [Vice President] Hubert Humphrey, Dow, the manufacturer of napalm, has become the most popular target for campus anti-war protests,” wrote Science magazine by the end of 1967. Protests mounted against Dow; they spread beyond college campuses. And the protests impacted Dow’s bottom line—Dow lost 5,000 shareholders in less than two years. Dow’s chairman felt that “a good many of the 5,000 we lost reacted in least in part to the napalm stories.” The protests indelibly marred Dow’s reputation. As historian Robert Neer—who wrote the book on napalm—argues, “Dow’s record as a manufacturer of napalm remains an important part of the company’s public identity.”1

The complicated financial instruments that compromise modern university endowments did not exist at the time. The protestors took on one company—Dow—and not an amorphous portfolio of obscure investments. The word “divestment” did not pervade the protestors’ lexicon, their slogans. But the goal of getting war profiteers off of college campuses, of limiting the power of private interests to dictate the public welfare, lie at the heart of their efforts.

Divestment was also connected to a broader left-wing movement for social change. Activists then, and now, wanted an end to war, but they also sought a greater reallocation of federal resources to address poverty and racism. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) hoped to be the vanguard of “an effort in understanding and changing the conditions of humanity in the late twentieth century.” The Vietnam War shook the foundation of American political order, of what was possible for the Left.

The protests at places like Columbia, UCLA, and Dartmouth have led to mass arrests, rollicked their campuses, and garnered significant media attention, but they are ultimately operating within the American political tradition described by Hofstadter. The goal of the protests is far from revolutionary: There are no calls to nationalize university endowments or even to force large, private universities to pay taxes, let alone to create a socialist utopia. Disinvestment in 2024 is coupled with demands for a cease fire, for an immediate end to American support for Israel’s war, which could be the basis for a broader peace movement. But the divestment movement, at its core, it seems, aims to make capitalistic investment more equitable and responsive to democratic pressures, to empower public constituents who fail to benefit from private gains. Divestment will not end the war in Gaza, but it will end the influence of private companies over what is a public good: a university education.

This is not to denigrate the protests. Nor is it to claim that the protestors are not motivated by broader concerns of social justice. They certainly are—it is readily apparent that protestors are connecting divestment to larger issues of racial injustice, of how they can rectify moral wrongs at home and abroad. This is only to say that the divestment movement (or moment?) of 2024 operates within a vein of American reformism that is familiar to the activists of the 1960s, but also to the “agrarian revolt” and the Granger movement of the late 19th century, the progressive anti-monopolists of the early 20th century, and the New Dealers who sought to rein in corporate excess through state regulation. The tactics among these reformers are different—those who operate outside the state have different tactics than those who function within it— but their tenor and strategic ends are similar.

This brings us back to Hofstadter. If we see the protests within the contours of the American political tradition, it makes it difficult to view the activists as the disaffected, misguided, and uninformed revolutionaries the media has portrayed them out to be. Moreover, if we place the students in the context of the American political tradition, however capacious, it reveals the extent to which the police response has been disproportionate to the goals of the protestors. The heavy police presence in these protests demonstrates the capacity and willingness of public-private institutions and networks (police working alongside universities) to repress activities that do not upend their power, but question its purposes—and demands reform. This phenomenon has much to do with what came after the 1960s: the militarization of the police and the neoliberal transformation of the university. The protestors demand a revision to the modern social contract in this context, to what is right and just in a democratic society. This demand is not inordinate; it is not exceptional in American political history. As Adam Tooze has written, after he witnessed the police response to the Columbia protests:

Once you have seen the working of coercive state power up close, you realize that slogans like defund the police do one vital thing, something which should be essential for democracy, they challenge not just the bargain to which we agree - do we divest? are wages acceptable? etc - the radical slogans challenge the coercive power that ultimately sets the playing field on which we bargain.

Perhaps the reaction to the protests tells us something about the fate of social democracy in the United States, about the prospects for left-wing movements. Indeed, the protests demand that we answer questions about their (our) future: Where does divestment go from here? Do the protests become something bigger? Will they exert influence over state power, over policy? Will they matter in a historical sense?

But to grapple with these questions, and try to answer them, we should think beyond the 1960s.

Much of the material on Dow is drawn from Robert M. Neer, Napalm: An American Biography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), chapter 7.